Whether military or civilian, both courts serve the purpose of dispensing justice. However, there is an ongoing debate and scrutiny in the media regarding the transfer of cases of ordinary citizens to military courts.

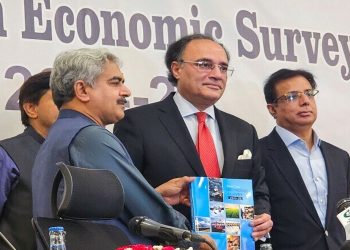

Recently, the Caretaker Prime Minister, Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar, in an interview given to a private TV channel, stated that having cases in military courts proves our loyalty to the state. If a decision is not in accordance with the constitution and the law, it is our duty to appeal.

Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar emphasized that those who attack defense installations should face trial in military courts. If someone attacks state institutions for political reasons, it cannot be ignored.

Kakar stated that those who attack state institutions should understand that they will not go unpunished. The events of May 9 are not political actions but fall under the categories of siege, unrest, and anarchy. Those who attack institutions should face trial in military courts.

The crucial question here is: What is a trial? What is the difference between a criminal and an accused? A criminal is someone on whom guilt has been proven, and an accused is someone against whom an allegation is made, either by the police, government officials, or a prosecutor, claiming that the person is a thief, dacoit, or murderer.

One does not become a criminal just by someone’s statement; it must be proven through legal proceedings that the actual crime occurred, and if the court convicts the individual or pronounces a sentence, only then can the accused be called a criminal and be held accountable.

On the other hand, a trial, meaning a case, always belongs to the accused, not the criminal, because once guilt has been proven, the purpose of the trial no longer remains. When someone is labeled a criminal during the trial, it means the accused’s entitlement has been compromised.

The painful reality is that on one hand, the court may grant bail to a person, while on the other hand, the police, the FIA or other law enforcement agencies may re-arrest that person in a different case, and the court cannot do anything.

If this is the state of civilian courts, what will be the treatment of the accused in military courts? Questions can be raised on this. The pillars of justice, legislature, and military authorities are crucial in the state. However, journalism is also considered the fourth pillar of the state.

Unfortunately, for the past 76 years, these pillars of the state have been entwined, and the people are unable to understand which pillar stands for justice and which for injustice. Who needs guidance, appreciation, and who deserves punishment?

For example, Pakistan’s power structure appears to be in the hands of politicians and, seemingly for an extended period, covertly under the control of the establishment. The military authorities govern the establishment.

The establishment’s job was not to govern, but for over 40 years, military rule has prevailed in the country, and former army chiefs either become martial law administrators or assume the title of Chief Executive of Pakistan, remaining the de facto rulers of the country.

On the other hand, the politicians’ job was legislation and implementing projects for the public welfare, but the Supreme Court, by taking suo-motu actions, started intervening in administrative matters, and politicians have been influencing the judiciary for the past 76 years.

In such a scenario, when the question arises about whether a case should be in civilian or military courts, it is essentially a question of basic human rights. As much trust as the people have in the pure army, the same should be on military courts. However, the intriguing question is why so much power is being given to military courts? Does the existence of civilian courts still serve any purpose or not?