MIAMI: A new spacecraft is journeying to the Sun to snap the first pictures of the Sun’s north and south poles. Solar Orbiter, a collaboration between the European Space Agency and NASA, will launch from Cape Canaveral on February 7, 2020

Launching on a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket, the spacecraft will use Venus’s and Earth’s gravity to swing itself out of the ecliptic plane — the swath of space, roughly aligned with the Sun’s equator, where all planets orbit. From there, the spacecraft’s bird’s eye view will give it the first-ever look at the Sun’s poles.

“Up until Solar Orbiter, all solar imaging instruments have been within the ecliptic plane or very close to it,” said Russell Howard, space scientist at the Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C. and principal investigator for one of Solar Orbiter’s ten instruments. “Now, we’ll be able to look down on the Sun from above.”

As of right now we are tracking a NET February 5th launch of @ulalaunch‘s Atlas V carrying the joint @NASA and @esa Solar Orbiter. @ESASolarOrbiter#SolarOrbiter #AtlasV pic.twitter.com/horn3DbpGn

— Geoff Barrett ???? (@GeoffdBarrett) January 25, 2020

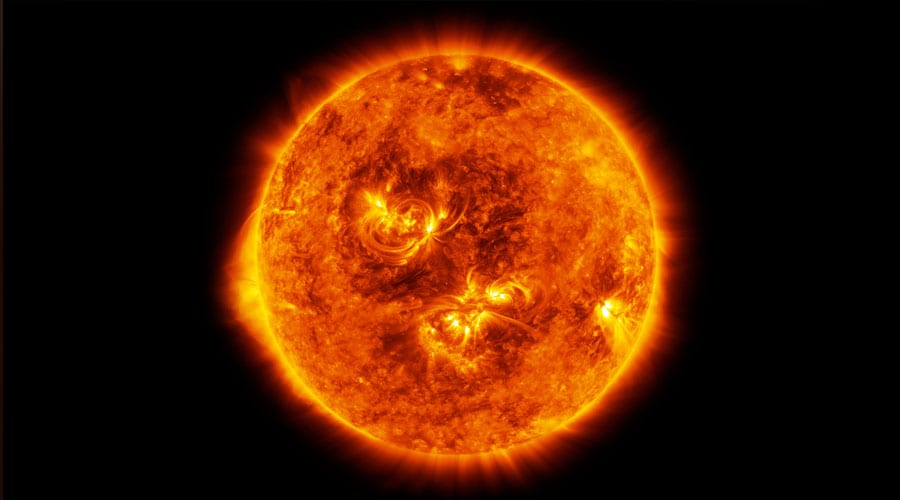

The Sun plays a central role in shaping space around us. Its massive magnetic field stretches far beyond Pluto, paving a superhighway for charged solar particles known as the solar wind. When bursts of solar wind hit Earth, they can spark space weather storms that interfere with our GPS and communications satellites — at their worst, they can even threaten astronauts.

“The poles are particularly important for us to be able to model more accurately,” said Holly Gilbert, NASA project scientist for the mission at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “For forecasting space weather events, we need a pretty accurate model of the global magnetic field of the Sun.”

What does it take to fly solo?

At its closest, #SolarOrbiter will come within about 42 million km of the Sun☀️

That’s closer than the scorched planet Mercury, just over quarter the average distance between the Sun and Earth, and closer than any European spacecraft in history pic.twitter.com/7hMJHUaMYR

— ESA Operations (@esaoperations) January 24, 2020

The Sun’s poles may also explain centuries-old observations. In 1843, German astronomer Samuel Heinrich Schwabe discovered that the number of sunspots — dark blotches on the Sun’s surface marking strong magnetic fields — waxes and wanes in a repeating pattern.

Today, it is known as the approximately-11-year solar cycle in which the Sun transitions between solar maximum, when sunspots proliferate and the Sun is active and turbulent, and solar minimum, when they’re fewer and it’s calmer.

“But we don’t understand why it’s 11 years, or why some solar maximums are stronger than others,” Gilbert said. Observing the changing magnetic fields of the poles could offer an answer.

The only prior spacecraft to fly over the Sun’s poles was also a joint ESA/NASA venture. Launched in 1990, the Ulysses spacecraft made three passes around our star before it was decommissioned in 2009.

????Launch update: @NASA @ESA & @ULAlaunch confirm #SolarOrbiter launch date adjusted to 7 Feb 23:15 EST/ 8 Feb 04:15 GMT/05:15 CET due to rescheduling of the Wet Dress Rehearsal earlier this week.https://t.co/EKs4UjH1QW pic.twitter.com/NKJg1scE2R

— ESA’s Solar Orbiter (@ESASolarOrbiter) January 26, 2020

Ulysses never got closer than Earth-distance to the Sun, and only carried what’s known as in situ instruments — like the sense of touch, they measure the space environment immediately around the spacecraft.

Solar Orbiter, on the other hand, will pass inside the orbit of Mercury carrying four in situ instruments and six remote-sensing imagers, which see the Sun from afar. “We are going to be able to map what we ‘touch’ with the in situ instruments and what we ‘see’ with remote sensing,” said Teresa Nieves-Chinchilla, NASA deputy project scientist for the mission.

After years of technology development, it will be the closest any Sun-facing cameras have ever gotten to the Sun. “You can’t really get much closer than Solar Orbiter is going and still look at the Sun,” Müller said.

Over the mission’s seven year lifetime, Solar Orbiter will reach an inclination of 24 degrees above the Sun’s equator, increasing to 33 degrees with an additional three years of extended mission operations. At closest approach the spacecraft will pass within 26 million miles of the Sun.

At its closest to the Sun, @ESASolarOrbiter will get within about 42 million km, closer than Mercury and closer than any European spacecraft in history. So how do we get #SolarOrbiter into this unique orbit at the centre of the Solar System? ???? https://t.co/x1siNjLQbN pic.twitter.com/PoTH22HlHS

— ESA (@esa) January 24, 2020