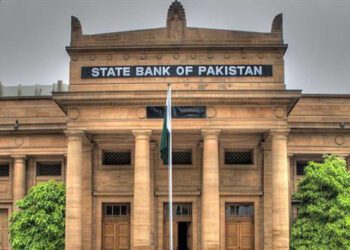

Pakistan is among the few countries today in deep financial trouble. The previous PTI-led indebted government spent money it didn’t have to shore up the tottering health system against the coronavirus pandemic, and to provide subsidies on petroleum products. Then the political drama in the wake of a no-confidence motion created unnecessary economic unrest. Moreover, Russia’s war in Ukraine sent wheat and petroleum prices surging and the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) began raising interest rates to quell inflation. After the new coalition government was sworn in, it contacted the International Monetary Fund (IMF) the last ray of hope for the country. Rising inflation, the balance of payment crisis, and the depreciation of the rupee have raised the concern of default for one of the most populous nations in the world.

A sovereign default occurs when a country is unable to repay its debts. Wars and revolutions, mismanagement, and political corruption are among the leading causes of sovereign default. In 2022, Russia was the first country to not repay its debts, due to financial sanctions. Sri Lanka remained in the news for defaulting on its debt. Pakistan, along with El Salvador, Ghana, Egypt and Tunisia, are at high risk of default. Lebanon defaulted in 2020 and Greece in 2015. Since Greece is part of the EU, it is akin to a poor man having wealthy siblings assisting him. Greece received an astronomical €289 billion in financial assistance from the troika consisting of the EU, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund. This enabled a return to financial normalcy. Pakistan is similarly expecting financial assistance from its wealthy cousin, Saudi Arabia.

The UAE had offered Pakistan $2 billion in exchange for minority shares in publicly listed government-owned companies. The UAE had struck a similar deal with Egypt earlier this year. These are all short-term measures as debt repayment cannot be sustained through undertaking further debt or by selling state assets. A sovereign default is hence very likely. All these defaulting countries had one thing in common, i.e. they lacked able leadership, who would practice fiscal responsibility and encourage economic growth. Sovereign default slows economic growth and bars further government borrowing from international investors for years.

Pakistan’s perceived risk of default has sharply risen to 79.33% in the wake of current political turmoil and uncertainty surrounding the ninth review of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout package. The country’s five-year credit-default swaps (CDS) increased from 7,550 basis points (bps) on November 15 to 7,933 bps on November 16, constituting a single-day of increase of 383.8 bps. The default risk perception stood at 7% in March this year. “Pakistan’s default risk is increasing due to multiple factors including a delay in the IMF ninth review, weak foreign exchange reserves and political turmoil. Pakistan needed at least $32 billion during this fiscal year to meet its foreign obligations and the government should secure the IMF review and required funds for the remaining fiscal year at the earliest to give confidence to the market and stabilize the economy.

Pakistan is currently in an IMF program and seeking further inflows to bolster its foreign currency reserves that have plunged to $7.959 billion as of November 17. The IMF staff mission is expected in Islamabad by the end of the month, but the date has not yet been finalized as the fund wants Pakistan to first make the required fiscal adjustments. The ongoing political uncertainty is also one of the reasons behind the day-to-day increase in the credit-default swaps as it shatters investor confidence in the market. The current increase in fuel prices and the inflation-led price hikes have affected all social classes. Previously, the rising inflation was more of rhetoric, but today it has become a painful truth with frozen wages and doubling prices. The

government has banned imports. Had it also banned extravagant weddings and put a cap on the prices of ready-to-wear clothing, then it would have been met with defiance. However, now there is no need for any directive from the state. Inflation will give impetus to modest living. Food shortages due to the Russian-Ukrainian war and climate change-related weather effects are an additional wake-up call. The earth does not possess infinite resources and when the human species gets out of control, the forces of nature subdue them. Pakistan should now redefine its priorities from consumerism and hedonism to responsible and conscious living.

Whether or not Pakistan defaults is contingent on the government successfully renewing the stalled Extended Fund Facility (EFF) program agreed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Access to international credit markets, funding from international multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, and bilateral financing arrangements are all tied to this.

As defined by the credit ratings agencies Standard & Poor’s (S&P), a country will default if it breaks a contract on a debt obligation or “tenders an exchange offer of new debt with less favorable terms than the original issue”. Should this happen, the ramifications for Pakistan will be devastating, as can be witnessed from the nightmarish chaos unleashed in Sri Lanka. Insolvency will cascade into the impoverishment of large parts of the domestic economy with accompanying destructive social dislocation.

The government and its institutions will suffer immediate loss in legitimacy among Pakistanis and international lenders. The impact of default is likely to ripple throughout the wider economy. Exporters and importers would no longer be able to obtain trade credit, causing shortages of crucial consumables and industrial inputs. As households experience increased unemployment, the level of overall consumption will fall, and therefore aggregate demand contracts. This in turn would mean even more workers will lose jobs, which will only exacerbate the demand contraction. It is far from certain that following a default, the state will be able to renegotiate the terms of the outstanding loans to enable it to revive access to international credit facilities, and work towards transforming the country’s economy in the long run without the burden of crippling debt.

The finance minister said that there were rumors that the country would not be able to pay $1bn on December 5 against the maturity of five-year Sukuk, or Islamic bonds. “We have never defaulted before. We will not even be close to default. Let me clear this categorically that the bond will be paid and there is no delay in this and even arrangements have been made in principal for upcoming payments in the next year. He said there was another rumor spread about fuel reserves depleting in the next few days. “There is nothing like this.

The reserves are present at the level they should be and there is no need for worry. Regarding the current account deficit, Dar said it was under strict watch and being monitored and managed for the national interest. He said it was $316 million in September and was expected to be below $400m in October. He reiterated that everything was in order and that bond payments would be made on time in the first week of December.